The new desire for the city.

The new desire for the city.

Farewell to urban pessimism

In the post-1968 era, urban pessimism about the future spread throughout Germany. Social research predicted the decline of cities and lamented their "inhospitable" atmosphere as a breeding ground for unrest. "Save our cities now!" was the dramatic demand of the German Association of Cities in 1971. All that is now history. The prevailing sentiment is more along the lines of: "The future is decided in the cities!" and "No state can function without cities!" Germans are rediscovering the quality of urban life, viewing city centers as livable spaces where people can feel comfortable. Almost three-quarters of the population (71%) appreciate historic city centers as tourist attractions, enjoy well-maintained green spaces and parks (71%), and are pleased with the good accessibility of city centers by public transportation (69%). This is the conclusion of a recent representative study by the BAT Leisure Research Institute, published under the title "Better living, more beautiful housing? Living in the city of the future" by Primus Verlag (Darmstadt).

From multigenerational housing to building cooperatives.

The population's hopes for the future

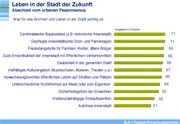

„In the public’s vision of the city of the future, it resembles a modern-day ‚Open Sesame,’“ says Prof. Dr. Horst W. Opaschowski, the institute’s scientific director and author of the book. „Almost everything that makes life in the city good, beautiful, and worth living is important and attractive.“ In addition to a diverse range of cultural offerings (67%) and a vibrant public life on streets and squares (66%), a high quality of life in the residential environment (64%) is desired. Cleanliness (68%) and a sense of security (62%) are just as essential to this urban well-being.

In the city of the future, people want to be able to realize new forms of housing, whether for rent or ownership – from co-housing projects and multigenerational housing to shared apartments for seniors. Multigenerational shared living arrangements will be one answer to demographic changes in Germany. Twelve out of every hundred Germans specify this desire very concretely: "My dream for the future is a shared apartment in a building where several generations have their own apartments and can come together in common areas at any time, but don't have to." These common areas will become extended children's rooms and offer working parents and single parents in particular more flexibility for supervision and care.

Professor Opaschowski: „Everyone under one roof – but each person in their own space. It's a form of living that is both communicative and individualistic, allowing for both togetherness and solitude while helping to prevent loneliness. This will also be a viable alternative for the growing number of singles and seniors.“ Interest in harmonious intergenerational living is increasing. Multi-generational shared apartments offer security and social comfort. They represent a sustainable housing model because they allow for both closeness and distance.

„"Lifestyle for rent!"“

The future offerings of housing companies

After clothing, one's home is considered a person's "third skin": status, self-image, lifestyle – everything is reflected there. The projected population decline will allow more freedom in the future to present oneself within one's desired social milieu. The question then arises more and more frequently: "Which home suits me?"„

One in four Germans (26%) wants to live in a residential complex in the future with neighbors who share "the same or similar interests." Will this lead to the proliferation of special residential areas exclusively for singles or couples, families, retirees, or immigrants? Opaschowski: "More and more people want to buy lifestyles, not just houses. Housing associations will then strive to offer residential developments with shared interests and guarantee a life among like-minded individuals." In such shared-use buildings, lifestyles are practically cemented. Here, those seeking help and those offering it, those seeking social interaction and those who enjoy socializing, can live together and side by side.

Changing lifestyles are shaping the future of housing: Flexible living is the order of the day. In a society of longevity, housing options are largely determined by changing life phases and are increasingly less a matter of social background (e.g., social origin, education) or wealth. Opaschowski: "Ideally, with each new phase of life, the house would have to be remodeled or redecorated. Those who change jobs or partners move elsewhere. And those seeking new like-minded individuals opt for a temporary shared apartment based on shared interests."„

From this perspective, standard apartments will soon be a thing of the past. Real estate is becoming more "temporalized"—as houses, apartments, or shared living arrangements for different phases of life: for families or single people, singles or seniors. More than one in four Germans over the age of 65 (27%) desires a shared-interest housing complex. These can also be innovative building cooperatives or shared living arrangements for seniors, where residents can live independently and autonomously in their own rooms while also having access to communal areas. Such shared living arrangements offer opportunities for communication and simultaneously guarantee social support in case of need for care. "Living differently" in the future means: not growing old alone, in contact with younger people.

Shopping. Scenery. Street cafes.

The sunny side of city life

Not every city dweller can afford everything. But it's clearly beneficial and contributes to well-being to be able to stroll around at any time without having to buy or own anything. One in two Germans associates the city of the future with a variety of shopping opportunities (52%) and good accessibility (43%). This is what makes city life so appealing: strolling through shopping arcades (49%), lingering in street cafes (36%), enjoying well-maintained green spaces (30%), pursuing education (29%), and attending cultural events (36%). This is the attractive side of urban life. Poverty and old age, fear and unemployment are temporarily forgotten. In urban life, people want to move about as far removed as possible from visible and tangible hardship and necessity. Here, people present themselves differently than at home—more consumer-oriented and sociable, more life-loving and adventurous. For many, city life means a change of scenery. A change of scene. Role reversal.

When everything is done – that's when city dwellers come alive. Then they want to experience something, and above all, themselves. Then they have free time and seek out leisure places – in green spaces, outdoors, and in the fresh air. But social meeting points for shopping, going out, and dining are also in demand. Opaschowski: "The urban leisure life of the future takes place between nature, culture, and cuisine. Parks, arcades, pubs, and bars are the most attractive leisure places in the city. They offer opportunities for relaxation and experiences, social interaction and consumption."„

City parks (91%) and recreational areas (87%), restaurants (87%) and cafés (84%), pedestrian zones (86%) and shopping arcades (83%) are among the most popular destinations for city dwellers. Amidst urban greenery, people seek to enjoy social interaction and culinary experiences, casual encounters, relaxed entertainment, and conviviality, as well as the pleasure of good food and drink. Traditional cultural institutions such as theaters (67%) and museums (65%), concert halls (60%) and art galleries (53%) are also included, although they are significantly less favored. For example, among 40 attractive leisure locations in the city, the opera house ranks last (43%). The indoor swimming pool (81%), the playground, and the sports facilities (each 78%) are rated much higher by the residents. Here, one can relax, be free and uninhibited. Nobody wants anything, nobody has to do anything.

Municipal deficits.

Complaints about the lack of child-friendliness and high rents

In Germany's major cities, children will become a minority in the future. Since 1900, the proportion of one- and two-person households in Germany has more than tripled, rising from 22 percent in 1900 to 70 percent in 2005. And since the mid-1960s, the number of births has halved, from 1.4 million in 1964 to 0.7 million in 2005. Germany is among the countries in the world with the lowest birth rate and the highest rate of childlessness.

Childlessness in Germany is not purely a private matter. It has deeper societal causes. There is a lack of positive role models and values in society that encourage having children. Furthermore, there is a lack of family-supporting services regarding housing, transportation planning, and leisure activities. This is one reason why most major German cities are rated as "not child-friendly" by their own residents – most notably Frankfurt (641), Essen (621), Dortmund (591), Berlin (571), Cologne (551), and Hamburg (541), and least not Bremen (361), Stuttgart (451), and Munich (471).

German citizens are experiencing a situation where local authorities are now almost exclusively managing existing problems. The cityscape is characterized more by potholes than by new buildings. In addition to potholes, criticism focuses primarily on shortcomings in child and family policy – from the lack of playgrounds (26%) and insufficient all-day childcare (26%) to family-unfriendly structures (15%). More than one in five respondents now notice neglected green spaces (23%) and feel repelled by the unclean cityscape (21%). And for some residents, citizen-oriented administration is just a pipe dream. Instead of working together to address local problems, a lack of cooperation is more noticeable (22%). Ultimately, this leads to cuts everywhere – in money and in community engagement.

The thought of life in the city of the future escalates problems – especially in the social sphere:

- Almost every second West German (46% – East German: 32%) expects high rents in the future that will hardly be affordable anymore.

- East Germans are primarily concerned about rising crime (42% – West Germans: 40%).

Both West and East Germans agree that the cityscape of the future will be characterized by stress and unrest (34% each) as well as by poverty and misery (27% each).

The population's anxieties about the future reflect the economic problems of recent years. Unemployment and the fear of job loss, coupled with concerns about retirement and pension security, are for the first time jeopardizing the maintenance of living standards (and not just quality of life). The issues at stake are existential: housing, food, and clothing. For one in three Germans (33%), one thing is clear: "The most important thing for me in the future is affordable housing in a central location." There is widespread fear of being forced out of the city against my will. Young people, especially those up to the age of 34 (39%), are unwilling to give up living close to the city center.

Professor Opaschowski: „The desire for ‚affordable housing in a central location’ is like squaring the circle. Experience shows that city living quickly reaches the limits of affordability.“ This desire is most frequently expressed by blue-collar workers (42%) and those with low incomes below €1,750 (36%) – knowing or suspecting that this wish will be difficult to fulfill in the future. This is where building cooperatives can help, where like-minded individuals plan together, act as developers, investors, and residents, and make affordable urban living possible.

Metropolises with character.

Quality of life ranking of the ten largest cities

Where is the best place to live? Residents of Germany's ten largest cities largely agree on this question: 85 percent of Germans consider their city to be a good place to live – although with significant variations ranging from 70 percent (Dortmund) to 91 percent (Hamburg). Germans also appreciate the diversity (82%) and cosmopolitanism (81%) of city life.

At the same time, they ruthlessly expose the social shortcomings of urban life: There is no longer a majority in the population for child-friendliness (46%), family-friendliness (49%), and senior-friendliness (49%). These are clearly the biggest challenges for life in the city of the future. Professor Opaschowski: „Local politicians have provided plenty of green spaces, a diverse cultural offering, and a wide range of leisure activities, but they have done too little to motivate and encourage people to interact respectfully with one another. In the city, ‚there’s always something going on’ and ‚everyone gets their money’. However, the social glue has often been forgotten.“

Many city dwellers seem to live in isolation, isolated from one another. City festivals and mega-events showcase cosmopolitanism and tourist appeal without fostering genuine human connection or neighborly bonds. The spectacle fades, and people drift apart again in social indifference. A city without a child-friendly atmosphere cannot have a sustainable future.

In the assessment of the residents – in each case comparing the ten major cities –

- Hamburg, the most beautiful and livable city,

- Bremen, the most cosmopolitan and atmospheric city,

- Munich, the most hospitable and leisure-friendly city,

- Berlin, the most culturally diverse city,

- Cologne, the most tolerant city and

- Stuttgart is the most economically powerful, wealthiest and safest city.

Bremen receives exceptionally high levels of approval from its residents for its urban atmosphere and its friendliness towards children, families, and the environment, achieving top scores unmatched by any other major city. Dortmund residents attest to their city's above-average transport and road network. While the capital, Berlin, may be a trendsetter in culture and politics, Berliners give their city a damning assessment in one respect: Berlin is considered the dirtiest city compared to other major cities. It is also striking that most major cities have not yet adequately responded to demographic changes: only a majority of Hamburg (611), Bremen (591), and Munich (541) residents consider their city "senior-friendly." In Berlin (481), Stuttgart (471), Essen (461), Düsseldorf (441), Dortmund (441), Cologne (391), and Frankfurt am Main, the figures are even lower. (35%) local politics has so far reacted too little to the consequences of the aging population.

„If cities want a future, they can’t just focus on their economic standing,“ says Professor Opaschowski. „It’s equally important to create a positive self-image among the population through internal marketing: hospitable, cosmopolitan, tolerant.“ What was initially planned to be achieved through elaborate national advertising campaigns in the run-up to the 2006 FIFA World Cup is already a reality in cities like Munich, Bremen, and Cologne.

Chosen families: Familyless people are „adopted“.

Outlook on the urban society of tomorrow

Anonymity, a lack of social control, and the hectic pace of city life have traditionally been considered hallmarks of an urban lifestyle. In the future, much will change: life in the countryside will become increasingly similar to city life. Both will be possible: the urbanization of villages and the ruralization of cities. Or, in planners' terms: densification and de-densification. Motorization and mobility are blurring the lines between city and country. The very definition of "city" is already becoming increasingly indistinct. Internationally, the minimum population for a city ranges from 200 inhabitants in Denmark to 30,000 in Japan. In Germany, over eighty percent of the population now lives in cities.

Fewer. Older. More diverse. This is what life in the city of the future will look like. The cityscape will be characterized by fewer children and teenagers, more older, gray-haired people, and a colorful mix of locals and immigrants from different cultures.

The era of urban exodus is coming to an end. Fewer and fewer people are living in rural areas. Declining quality of life in the countryside and extremely high energy prices are accelerating the trend of moving "back to the city." Inner-city residential areas are more likely to offer a feeling of being "fully provided for." Looking ahead, Germany will remain in flux. Architects, planners, and investors should prepare for this development in good time and focus more on centrally located residential areas. In particular, people in the post-parental phase of life ("45+") are turning their backs on commuter towns and suburban housing developments, seeking, for their own security, the guarantee of a diverse range of work, leisure, cultural, and social services close to home.

The city of the future offers short distances, more choices, and a higher quality of life and experience. Tomorrow's urbanites want to live 'right in the heart of things' and be open to new lifestyles and co-housing communities. Together, they become the architects, planners, and designers of their own houses and apartments. Through self-help and neighborly support, they foster stable social relationships within their neighborhoods ("civic life").

Perhaps, as in previous centuries, the idea of the "whole house" will be revived because people will remain interdependent and need to be more self-reliant. In the future, the "whole house" won't just accommodate family members. Grandchildren, children, and those without families will also be integrated into the community "as if through adoption," forming new chosen families. In this way, everyone could lead a self-determined life—but not alone. Together, not alone, is the housing and living concept for the city of the future: more intergenerational housing and co-housing than nursing homes and assisted living facilities.

The book

HORST W. OPASCHOWSKI

Live better, live more beautifully?

Life in the city of the future

265 pages/51 graphics/index

is available in bookstores now:

ISBN 3-89678-544-3 Primus Verlag Darmstadt 2005

19.90 euros